Sheep Health Page

(With special consideration to Scottish Blackface Sheep)

Foot Rot in Sheep

Foot Rot is a problem often overlooked by shepherds and sometimes taken too lightly as a cause of monetary loss and loss of thriftiness in sheep. Once loosed in a flock, foot rot can become a persistent reoccurring nightmare. The Shepherd should take notice and act aggressively at the first sign that foot rot may be present in a flock. Foot rot is often in the soil on fair grounds and auction barns and all newly purchased sheep and sheep coming home from fairs or shows should be penned separately and inspected for foot rot. Keep the feet of your sheep trimmed so there are not pockets for the bacteria to thrive. There are a number of copper and zinc based products on the market to treat foot rot and scald as well as a vaccine that is fairly effective. It is wise to trim feet when the sheep are being sheared. Often hooves become overgrown after a winter indoors on soft bedding, or while penned in yards when there is no pasture available. It is under these conditions foot rot can spread to the entire flock. It is best to isolate individuals with foot problems. These animals should have their feet treated aggressively and they should not be returned to the flock until all signs of infection are gone. Some sheep are known to be carriers of foot rot and it is best to cull these individuals. Consult your veterinarian for the best course of action should foot rot become a problem on your property. There is a new plague in the UK of a virulent form of foot root that attacks the coronary band of the hoof, it is known as CODD. If you live in the UK be aware of this new threat to your flock. There is some preliminary findings point to the fact this infection may be crossing over from cattle to sheep.

Keep feet trimmed to prevent infection.

Tail Docking

If you choose to dock tails the docked tail needs to be long enough to wag! This may surprise some shepherds, but if the tail is left long enough to be raised, it lifts the supporting tissue around the anus and, like a cow’s tail, directs any diarrhea away from the body. If the tail is amputated close to the body, any diarrhea runs down the back end, soiling the skin and fleece. So the tail should be left long enough to cover the vulva or the equivalent length in males. Lambs from the Northern European short-tail breeds like Shetlands or Icelandics do not require docking. There are many who choose not to dock Scottish Blackface Sheep as the tail ends at the hocks unlike many commercial breeds where the tail very nearly drags on the ground. Sheep lift their tail when they defecate and use their tail, to some extent, to scatter their feces. Docking the tail too short is more of a risk to a ewe than not docking. Tail docking is done to prevent flystrike. First the flies eat the manure on the wool but then actually attack the flesh of the tail. This is more of a problem with sheep on rich pasture or those fed high concentrations of grain.

Undocked Scottish Blackface Ram lamb USA and undocked lamb in Germany

Sheep Tail Length

Author: Dr. S. John Martin - Veterinary Scientist, Sheep, Goat and Swine/OMAF

Again the argument on the length of the tail dock in sheep has surfaced. The tail has many functions; the tail at the full length in the ewe, will protect the udder from chilling. A Scottish Blackface on the hill retains all the tail, because the shepherd knows that in the extreme conditions that the ewe will be raising her lamb, the udder needs protection to prevent chilling and possible mastitis. Very often, when a sheep is defecating, it will shake the tail to spread the fecal pellets.

But what happens if the tail is left long on our lush pastures. Soft feces collect under the tail, making an ideal site for fly strike. Flies lay eggs in and around the fecal mass, hatching into maggots which will attack the flesh under the tails, even entering the rectum and vagina. A lamb with fly strike is not a pretty sight and will almost certainly die.

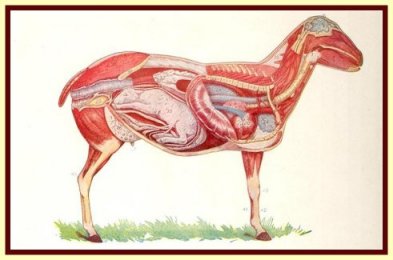

However, completely removing the tail to prevent fly strike has its problems too. Certainly, some rectal prolapses may be genetic in origin, but many are the result of this tail removal. The problem lies in the anatomy of the region; the anus and the vulva are held closed by sphincter muscles, circular muscles round these openings, which relax to allow feces and urine to be passed. To have strength, any muscle must be attached to a bone of the skeleton; these muscles have two attachments to the underside of the tail bones. One runs forward and the other back along the tail. When a tail is docked short, the rear muscle attachment is removed, thus weakening these muscles.

The weakness may not be apparent immediately, but very often a tailless sheep will invert the rectum when passing feces. Eventually the rectum will not completely return, leading to a prolapse. In the late 80s, the vogue was for tailless sheep, and there was a significant problem with prolapsing ram lambs in the test station. As tails were left longer the problem disappeared.

Every year at lambing, there are queries on prolapsing ewes in the last month of pregnancy. In many cases a contributing factor is a short dock and the loss of half the muscle attachment. In the last month of pregnancy, the muscles of the pelvis including the retainer muscle of the vagina and the sphincter muscle of the vulva are relaxing under the influence of hormonal change in preparation for lambing. An already weakened vulva muscle is made weaker by these hormonal changes; the result is a vaginal prolapse. Of course, prolapses will occur in ewes with longer tails because of other factors, such as selenium deficiency at this stage of gestation.

Each method of docking, the rubber ring, the knife, the Burdizzo and knife will produce the same results if performed with care and correctly. At the moment the recommended site is at the end of the web underneath the tail. As this may leave too short a tail in the adult ewe, work is underway to determine the correct site.

The Code of Practice recommendation to dock to the lower lip of the vulva in ewe lambs and to below the rectum in the ram is a compromise between no dock, with the risk of flystrike, and a complete dock with the possibility of rectal and or vaginal prolapse. This recommendation was agreed to by the committee which included producers, veterinarians, and members of the humane society with input by provincial sheep associations. This compromise also addressed the concerns of the humane movement that docking was an unnecessary mutilation. So the question remains, why to continue to very short dock or completely remove the tail when the compromise length satisfies the health needs of the sheep?

Natural Tail on a Blackface Ewe Lamb

.

|

Horn Problems

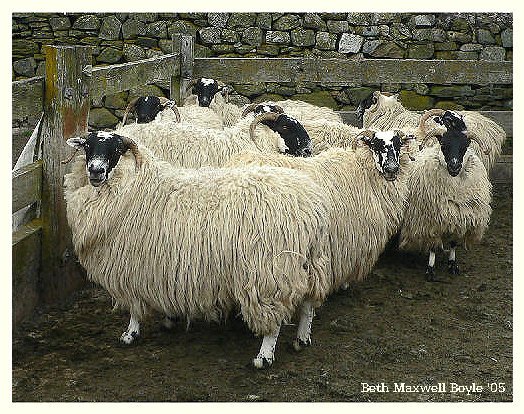

Horns should be well away from the face as seen on these hoggs

Horns should be away from the face, close growing horns cause sores and can restrict a sheep from eating properly. In the USA breeders are struggling to breed away from animals with close growing horns. In Scotland it is not nearly the problem it is in the US. Horns can be trimmed but care must be taken to stop short of the live core. Obviously it is better to breed sheep with horns that do not need trimming than to have to trim horns that persistently present a problem. In the highlands of Scotland it's hardly practical to chase down large numbers of sheep to trim horns! On the other hand a little trimming on certain individuals is not really difficult if it is necessary. Often just one trim and the animal is never bothered by close growing horns again. Take care to use fencing with horned breeds that does not present the risk of injuring or killing sheep that try to graze too close to the fence. Many sheep die when their horns tangle them in fences.

It's interesting to note that in cold climates heat loss through the horn surface may be substantial. The internal core of the horn contains many blood vessels, while the outer keratin sheath presumably offers little the way of insulation. Considerable amounts of heat can be lost through the horn surface, particularly in the large-horned species. Horns are thought to play a thermo regulator role as heat-dissipation structures and benefit the animal in hot weather, but this heat loss may be detrimental in winter. The largest surface area that the animal can afford to sustain through the winter may limit horn size.

The skull shows the bone core inside each horn.

Vaccinating

You should be aware of what sheep diseases most affect the sheep in your area and vaccinate accordingly but one thing is certain you should vaccinate to prevent tetanus and C and D perfringes infection. A combination vaccine is available that can protect your growing lambs from infection. Tetanus must be prevented from moving up the umbilical cord so you should dip the cord in iodine at birth and vaccinate you ewes at least three weeks prior to lambing. Tetanus can also infect your sheep during docking and castration. If you vaccinate with a combination vaccine for C&D plus tetanus your sheep will also be protected from "Overeating disease" or Enterotoximia. Enterotoxemia type D is most commonly associated with heavy concentrate feeding or an abrupt change in the diet, usually to a better feed. It usually affects weaned lambs that are consuming at least 3/4 of a pound of grain per day. In contrast, enterotoxemia type C most often affects nursing lambs within the first few weeks of life, causing a bloody diarrhea.It often strikes your biggest and fastest growing lambs. The vaccine is very inexpensive and it is very foolish not to inoculate your ewes prior to lambing as well as your lambs.

Worms and Parasites

We have found that some dewormers on the market have become relatively ineffective. Often internal parasites develop a resistance to deworming products just as bacteria develop a resistance to certain antibiotics. Currently, we rotate ivermectin with fenbendazole or albendazole and have been well satisfied with the results. But no one product will necessarily destroy all types of parasites, and parasite problems vary from one locale and climate to another. Many types of dewormers, although very safe and effective, are not labeled for use in sheep. You should seek your veterinarian's advice as to which product(s) are appropriate for your area and flock. He/she can legally recommend extra-label use of products packaged for other species. Dewormers come in a variety of forms: bolus (large pill), paste, liquid, pour on, and injectable. Most products come with directions and/or applicators for administering the dewormer. We personally have found the paste or liquid forms to be the easiest to use. Ewes should be wormed at breeding time and again before lambing if possible. Lambs have limited immunity to parasites and should be wormed at weaning age and watched closely for signs of reinfection. If possible turn your lambs out on pasture that has not been grazed by adults that season.

Scrapie

There has never been a case of natural occurring Scrapie in a Scottish Blackface Sheep. In a controlled study in the UK goats and Blackface were infected by researchers but there is not one documented case of naturally spread scrapie in a Blackface raised in the USA or the UK. Scrapie, an invariably fatal disease of sheep and goats, is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE). The putative infectious agent is the host-encoded prion protein, PrP. The development of scrapie is closely linked to polymorphisms in the host PrP gene. The pathogenesis of most TSEs involves conversion of normal, cellular PrP into a protease-resistant, pathogenic isoform called PrPSc. The conversion to PrPSc involves change in secondary structure; it is impacts on these structural changes that may link polymorphisms to disease. Within the structured C-terminal part of PrP polymorphisms have been reported at 15 and 10 codons of the sheep and goat PrP genes respectively. Three polymorphisms in sheep are acutely linked to the occurrence of scrapie: A136V, R154H and Q171R / H. These generate five commonly observed alleles: ARQ, ARR, AHQ, ARH and VRQ. ARR and AHQ are associated with resistance; ARQ, ARH and VRQ are associated with susceptibility. There are subtle effects of specific allele pairings (genotypes). Generally, more susceptible genotypes have younger ages at death from scrapie. Different strains of scrapie occur which may attack genotypes differently. Different sheep breeds vary in the assortment of the five alleles that they predominantly encode. The reason for this variation is not known. Furthermore, certain genotypes may be susceptible to scrapie in some breeds and resistant in others. The explanation is not known, but may relate to different scrapie strains circulating in different breeds, or there may be effects of other genes which modulate the effect of PrP. There is no treatment, although the disease was eradicated from Australia and New Zealand by compulsory slaughter of imported sheep and flockmates shortly after release from quarantine. After the disease first appeared in the USA (in 1947), the Scrapie Eradication Program was established. This involved identification of affected animals and destruction of all sheep in the flock as well as other exposed flocks. This procedure was modified in 1983 to destroy mainly bloodline animals because of the strong familial occurrence of the disease. The current program in the USA is based on active, passive, and slaughter surveillance with removal of genetically susceptible sheep from flocks in which scrapie is detected. An eradication scheme has begun in the UK based on PrP gene susceptibility. It aims to replace scrapie-susceptible PrP alleles with more resistant ones, thereby controlling and eventually eliminating the disease from the national flock .In the USA the Suffolk and Hampshire present most cases of Scrapie and the Scottish Blackface none. For this reason it would be honest to relate to potential customers that Scottish Blackface meat is very safe to consume both in the USA and UK.

Caseous Lymphadenitis

Caseous lymphadenitis, which is caused by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, is a widely spread disease of mature sheep and a major reason for condemnation of ewe carcasses. The abscesses occur in the lymph nodes and may affect the lungs, liver, kidneys, and spleen. Shearing wounds are the major cause and means of spreading the disease. To minimize spreading the disease, shear lambs first and disinfect shearing clippers. C. pseudotuberculosis can survive for months in organic matter such as bedding. The typical pathogenesis of the disease is that the bacteria gain entry into the animal from a wound such as a shearing nick or a nail poking out of a fence. The bacteria will then localize in an abscess that the animal walls off from the rest of its body. The clinical signs of the disease is one or more abscesses that are often located just beneath the skin. However, if the bacteria is spread throughout the bloodstream, abscesses may also develop in internal body organs such as the lungs. In this case superficial In regards to treatment, antibiotic treatment is ineffective due to the inability of any antibiotic to get inside the abscess. The best therapy for superficial abscesses is to lance the abscess and flush the inside of the abscess with iodine. The material or pus that is present in the abscess should be disposed of in such a way as to avoid contamination of bedding to prevent further infection. Many shepherds will isolate the affected sheep, lance the abscess in an area where the sheep are not kept, and keep the sheep isolated until the wounds heal. Often the abscesses are not found until shearing time when the shearer inadvertently nicks wall of the abscess. If this occurs shearing should stop and the equipment and shearing carpet should be disinfected as well as possible. Also, to prevent infection in young sheep the shearing order should be the youngest to the oldest. The vaccine for sheep against C. pseudotuberculosis that is available is called Case-Bac and is manufactured by Colorado Serum. A recent study published in the June 1, 1998 issue of the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association showed a significant reduction the number of abscesses. In this study, the researchers took bacterial cultures and inoculated the sheep in numerous places including the lips and skin. After twenty weeks the sheep were euthanized and the carcasses were examined for abscesses. Vaccinated sheep had on average 1.3 abscesses compared to 33.1 abscesses in the control sheep. A side effect that we have seen with use of the vaccine is that this product causes a large number of injection site lesions or abscesses. Therefore if a farm has not had problems with caseous lymphadenitis in the past, vaccination is unnecessary. In farms that have serious continual problems, vaccination along with isolation and sanitation is beneficial. CLA was initially introduced into the UK in 1990 via goats, and since then has passed into sheep (1991) and increased in incidence, particularly in the pedigree sheep population.

Mastitis

Mastitis (acute pasteurella) is the major reason producers cull ewes. Mastitis is associated with lambs with sore mouth and incorrect "drying up" of the ewe at weaning. Minimize reinfection by isolating the infected ewe and her lambs. Palpate udders in the fall and cull ewes with indications of scar tissue. Mark infected ewes at lambing time. Avoid udder injury, and cull ewes with pendulous udders. Treatment includes giving sulfamethazine at one grain per pound of body weight (two bolus), intramammary infusion of the udder (by a teat tube), or intramuscular injection of 8–10 cc of tetracycline.

Sore Mouth

Contagious ecthyma (CE), also known as sore mouth or orf, is an acute infectious disease of sheep characterized by sores and scabs on the face, eyelids, teats, feet, and occasionally inside the mouth. animals may become infected more than once in their lifetime but repeat infections usually occur after a year's time and are usually less severe.The disease is widespread in the sheep population and affects all breeds. Infections occur in the spring and summer and heal in about a month. Humans who work around the sheep sometimes become infected. Currently, there are commercially available preparations of live virus marketed as vaccines. NOTE: All sore “mouth” vaccines contain live virus which, if proper protective measures are not taken, can cause infection in humans.

Copper Toxicity

Copper toxicity is a big concern for sheep, because it is a required mineral but is also toxic to them as well. This can vary based on breed, age, health status, levels of other minerals in body and in diet, and levels of ionophores in the diet. Copper is found in the feeding supplement for cattle and swine diet. If mixed with or fed to sheep, it can have drastic effects. There are two types of copper toxicosis; acute and chronic. Acute is when a high level is ingested in a short period of time. Chronic is when a low level is ingested over a long period of time, and exceeds the threshold level and escapes into the bloodstream. Excess copper is stored in the liver. Eventually hemolytic crisis occurs due to the destruction of red blood cells. Prevention is key in this disease. There are several key factors in prevention which include no feeding swine, poultry, or horse diets to sheep, communicating with your feed suppliers, testing your feed for levels of copper, molybdenum and sulfate, avoidance of pasture that has been treated with swine or poultry manure, and doing post-mortems on dead animals from your flock. The major symptom of copper toxicity is death in your herd. But symptoms may include animals go off feed and become weak, mucous membranes and skin are yellowish-brown, and/or urine will be reddish-brown and hemoglobin will be present. Treatment should involve your veterinarian. Treatment includes feeding or drenching with ammonium molybdenum, sodium sulfate, and penicillamine.

Ovine Progressive Pneumonia, or OPP

Ovine Progressive Pneumonia, or OPP, is caused by a virus and is prominent in the United States . This type of virus is very similar to Maedi-Visna, a retrovirus found in different parts of the world. A study found that 26% of sheep in the United States are infected with OPP, but the prevalence of the virus is largely dependent on flock management, the strain of the virus, and the genetics/breed of sheep. In fact, sheep and goats seem to be the only species that can naturally contract the OPP virus. Breeds which have been found to be highly susceptible to the OPP virus in the United States include Border Leicester, Finnsheep, Finn-crosses, Corriedales, Dorsets , and North Country Cheviots. Texel sheep are only susceptible in Europe , and the Ile de France has even been shown to be resistant to infection and disease. This suggests a difference between the pathological potency of the OPP virus rather than just the genotype of the sheep.

Transmission of OPP is mainly by ingesting contaminated milk/colostrum, like if a lamb receives milk from an infected ewe. Respiratory fluids, like from coughing, can also be transmitted between closely confined sheep. Signs and symptoms of OPP can begin to be noticed around two years of age or older because the disease progresses very slowly. Unfortunately, once signs are spotted, it is often too late to fix the problem. Two common signs are weight loss and lethargy when required to exercise more than usual. Breathing becomes very laborious and difficult for the sheep. OPP can be diagnosed by the presence of the virus or antibodies in the blood. A perfect diagnosis can only be made during necropsy, where the lung is covered in large lesions and discolored to grayish-blue. There are currently two different tests that can be used to detect the virus in live animals: Agar Gel Immunodiffusion Test (AGID) or the Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) test. AGID is able to detect circulating antibodies in the blood, but it should only be tested after six months of age, once the colostrum-derived antibodies are no longer present. The ELISA test is more sensitive than AGID as it can detect OPP only two weeks after infection. There is no treatment for such a virus. There are, however, two methods to prevent future exposure of OPP. One method of prevention would be to remove lambs from infected mothers before they have the chance to nurse from them. This is the start of an OPP-free flock and should never come in contact with infected sheep. The second method would be to test and remove all infected sheep and lambs that test positive for OPP.

Tetanus

Tetanus is a common, fatal disease in sheep and goats caused by a bacterium known as Clostridium tetani. The spores of this bacterium can be found in feces, they produce a powerful toxin in open wounds, and are not affected or destroyed by disinfectants. Most often, tetanus is caused by infection of an open wound. Because sheep undergo several maintenance procedures, such as castration, ear-marking, tail-docking, dehorning and debudding, sheep are highly at risk for contracting tetanus. Dog bites or deep scratches can also be "homes" for the bacteria. Incubation of Clostridium tetani is between 3 days and 3 weeks. During this time, the bacteria multiply and generate this powerful toxin. This toxin then affects the nerves around the site of injury/wound, travels to the spinal cord and brain, and ultimately causes uncontrollable muscle spasms. Consequently, signs and symptoms of tetanus infection include muscle stiffness and spasms, bloat, panic, uncoordinated walking and movements, and/or the inability to eat and drink. Death is inevitable, about 3-4 days after symptoms appear. Many sheep in a flock can be found dead without having shown any signs of the disease.

The risk of contracting tetanus can be prevented through cleanliness and vaccinations, such as tetanus anti-toxin and penicillin. Treatment, once the animal is already sick, can be very expensive and not very effective; this is why prevention is extremely important. The correct vaccinations are given twice around 4 weeks apart. An annual booster is recommended. A single vaccine will do little to build long lasting immunity in the lamb; therefore, it is important that the animal is fully vaccinated and protected before any type of surgical procedure.

Enterotoxemia (overeating disease)

Enterotoxemia in sheep can be fatal. It results from the sudden release of toxins by the bacteria Clostridium perfringens type D in the digestive tract of sheep. Enterotoxemia affects sheep of all ages, but it is most common in lambs under 6 weeks of age that are nursing heavy-milking ewes, and in weaned lambs on lush pasture or in feedlots. Creep-fed lambs and sheep being fitted for show are often affected. Frequently, the most vigorous lambs in the flock are lost. In unvaccinated feedlot lambs, approximately 1 percent of the lambs can be expected to die from this disease, with an average of about 2 to 3 percent. In severe outbreaks, losses may range from 10 to 40 percent.

The bacteria that cause the disease normally are present in the intestine of most sheep. Under circumstances generally brought about by heavy feeding, the Clostridium perfringens type D bacteria grow rapidly and produce a powerful poison (toxin) that is absorbed through the intestine wall. Death typically occurs within only a few hours, often before the owner observes any sick animals.

Conditions that can bring about enterotoxemia include changing feed suddenly, feeding excessively high energy diets, feeding irregularly, increasing the grain content of the ration too rapidly, not providing enough space at the feed-bunk, and feeding lambs of different sizes together. Heavy internal parasite burden also can cause this condition.

Occasionally, animals may be observed sick for a few hours before they die. Affected lambs frequently exhibit nervous symptoms, their heads are drawn back, and they exhibit convulsive grinding movements of the teeth, congestion of mucous membrane of the eye, and frothing at the mouth. In addition, diarrhea may be present shortly before death.

There is no satisfactory treatment for this affliction, but there are some preventive measures. Prior to placing lambs in a feedlot, vaccinate them with a Clostridium perfringens type D bacteria or toxoid. Allow at least 10 days after vaccination for immunity to develop. Under certain conditions, a booster shot is required two to four weeks later. Fast-gaining lambs grazing pasture or on creep feed may require a vaccination at 6 to 8 weeks of age. If they continue on high-grain rations, revaccinate them after weaning. Losses may be prevented in young lambs up to 6 weeks old by vaccinating the ewe during pregnancy. Ewes that have not been vaccinated previously should be vaccinated twice, two to four weeks apart, with the second vaccination administered two to four weeks before lambing. An annual booster two to four weeks before lambing is advisable.

BLOAT

Bloat is a condition where the lamb is unable to belch up the gas which is formed in the second stomach (rumen). The pressure will build up until it interferes with the lambs breathing and heart and he can die. It is caused by certain alfalfa hays, clover and alfalfa pastures. It can also be caused by a rapid change in diet or too much grain.

The lambs abdominal area (belly) will be very swollen looking, particularly on the left side. The left side will often be higher than the top of the back. The lamb will be uncomfortable and depressed. This is an emergency situation. You need to get the lamb to the veterinarian as soon as possible.

Bloating is one of many problems a stressed lamb faces. Lambs that can't/don't get colostrum at birth have a nearly zero chance of survival. Keep a frozen supply of sheep colostrum from ewes that had singles or ewes that lost their lambs. Small plastic soft drink bottle make good storage and feeding containers. Use a lamb tube to feed a new born lamb in stress a couple ounces of sheep colostrum.

The cause of bloat can be divided into three categories:

1. Frothy bloat - caused by diets that promote the formation of stable froth.

2. Free gas bloat - caused by diets that promote excessive free gas production.

3. Free gas bloat - caused by failure to eructate (belch).

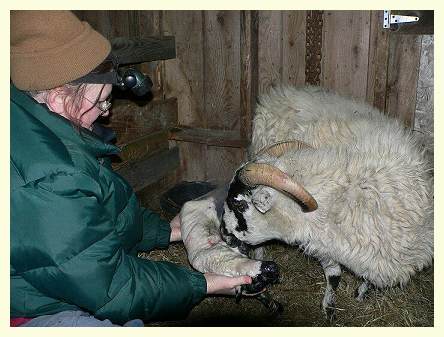

Lambing

Lambing season is the critical time when shepherd's skill, effort, and concern determine the success of their entire operation. Dozens of problems can occur. Most of these however, stem from poor management, inadequate equipment, or an indifferent attitude. Of the three, attitude is by far the most important, followed by management. Poor equipment often gets the blame, but good management and proper attitude can make even poor equipment work. Lambs are born about 145 days after the rams are turned in with the ewes. A new lamb is a 7- to 14-pound sopping wet baby that has left a warm, well-nourishing environment for a harsher life outside. Now it must initiate breathing, maintain its body temperature, and conserve its body fluids. However, it can't do any of these things if parturition is unduly delayed, if the lamb was undernourished in utero, or if the new environment is too cold . Newborn lambs primarily dry themselves by burning body fat that generates sufficient heat to evaporate the moisture from their skin and fleece. If you can't provide the lamb with a suitable environment don't "lamb" until the weather is warmer. The extremely critical time is from birth until the lamb is completely dry. Thereafter, a dry, draft-free area will suffice. Be sure your lambing kit is ready well ahead of time. If you are planning an early lamb crop you need to take the time to be on duty even at night to ensure losses do not occur simply because of the freezing temperatures in your barn!

Pregnancy Toxemia and ketosis

Risk Factors for Pregnancy Toxemia

Multiple fetuses

Poor quality of ingested energy

Dietary energy level

Environment

Genetic factors

Obesity

Lack of good body condition or high parasite load

Confinement - lack of exercise

Ewes suffering from pregnancy toxemia (ketosis) appear lethargic, sluggish and often fail to eat. The first symptom noticed in ewes is a unwillingness to eat. They become depressed, weak and have poor muscle control and balance later in pregnancy. Many times, when they lie down, they are unable to rise. Early in the disease, ewes will show a positive test for ketone bodies in the urine. The breath of does and ewes will have a sweet or foul smell. Ketone bodies are by-products of fat breakdown found in the blood and urine. Test kits are often available for ketone bodies and they are easy to use Pregnancy toxemia is caused by the sudden extra demand for energy by the fast-growing kids or lambs in the last few weeks of pregnancy. Seventy percent of fetal growth occurs during the last few weeks. The disease is not normally observed in ewes carrying singles. It is usually seen when the ewe is carrying two or more lambs. Does and ewes that are too fat often will experience pregnancy toxemia. At the time when the kids or lambs are growing very rapidly, increasing amounts of space and energy are needed, in addition to the protein and energy needed for maintenance of the doe or ewe. The increase in feedstuffs high in energy must be supplied on a daily basis. Does or ewes consuming large amounts of hay need a greater internal space in the rumen, which causes decreasing space for growth of the kids or lambs in the uterus. In meeting the nutritional needs of the kids or lambs, the doe or ewe will metabolize or break down fat resources from her body to maintain pregnancy. This rapid breakdown of body stores of energy produces ketones (a toxic by-product) and you soon observe the symptoms of the disease.

Maintaining ewes in a medium body condition rather than overly fat condition early in pregnancy will help keep down the disease.Toxemia and ketosis are typically seen in ewe that are overweight and get little exercise. Under weight animals that are fed a poor quality feed are also candidates for toxemia. Look for ewes at the bottom and top of the pecking order. These ewes may be getting too much or not enough feed. Ewes should be in good body condition, and not overly fat when bred. They can be maintained on good roughage or forage during the first 100 days of pregnancy. During the last trimester the ewe should gain approximately 1/2 lb. per day. The ewe must intake enough carbohydrates to supply the demand of the growing fetuses and to keep her alive and functioning also.

If you are not an experienced shepherd and you suspect your ewe is in ketosis do not wait call the vet immediately! You must treat the ewe very quickly or she will certainly die. Often its too late before you even realize your ewe is in ketosis and the outcome is not very positive so DO NOT WAIT!

This article was written for goats but the facts are pretty much the same for sheep and this is so excellent it is invaluable when you have a ewe in trouble

Lambing Kit Items

A LED headlamp will hold up for hours and free your hands in the case you need to assist a ewe during a difficult delivery.

Headlamps are perfect for dark sheep sheds.

These screw onto a soft drink bottle. They are shaped like a ewe's nipple. They have a metal valve inside that allows air to flow in smoothly but controls milk flow. You will never want to use anything else once you have used one of these.

This is sold in powdered form and should be stored in the freezer if kept for any period of time. Always use a quality sheep milk replacer. Cow replacer is too low in fat and sugar. This is one place you should never cut corners. Don't use a replacer labeled for goats or cattle. One to two day old lambs should be fed a minimum of 4 times/day. The fat globules in lamb's milk must be homogenized, and calf milk replacer contains excessive amounts of lactose, which may cause severe scouring and death loss. The compositional breakdown for a high quality lamb milk replacer is as follows: crude protein - 22 to 24%; crude fat - 25 to 35%; crude fiber - 0.5 to 1%; lactose - 22 to 25%; ash 5 to 8%; Vitamin A - 20,000 IU per pound; Vitamin D - 5,000 IU per pound; and Vitamin E-50 to 100 IU per pound. Because of the high fat content in milk replacer powder, it should be mixed in warm water using a hand whisk. Once in suspension, it should be cooled and stored at 35 to 40ƒ F. Cold milk at the time of feeding has been shown to reduce spoilage and results in frequent sucking of small amounts of milk replacer, which mimics a lamb's normal nursing behavior. Consequently, problems with abomasal bloat and digestive upsets are minimized. Milk can be kept cold by placing a bottle of frozen water in the milk reservoir twice a day. When cold milk replacer is used, milk containers and nipples should be disassembled and cleaned with warm soap and water once every two to three days. To prevent unnecessary loss of expensive milk replacer, worn and leaking nipples should be replaced immediately from a supply of nipples that were purchased beforehand. There are a number of very good brands on the market but read the labels carefully and select only a replacer with the qualities outlined above. Over feeding kills. Follow the directions on the bag carefully and step up the amount fed slowly.

Have on hand some penicillin, streptomycin, etc., for infection of the ewe or lamb.

Have on hand for antibiotics should you need to administer them.

Iodine is used for treatment of the navel. This will safeguard your lambs from Tetanus and bacteria that can be deadly to a lamb.

Wear these to prevent infection. Also remember to take off your rings if you are wearing them. Gloves protect you and the ewe.

This will help you gently slide your hand inside a ewe in the event of an abnormal presentation. Take care to scrub and wear gloves.

This can be a good item to have on hand if a chilled or orphaned lamp is too week to nurse. Keep this clean in a ziplock bag or some other container that will keep it spotless. A number of commercial tubing devices are available. The simplest is a 60 cc (2 oz.) syringe and catheter. Tubing should be 14 to 18 inches long (long enough to extend from the lamb’s last rib to its mouth plus approximately another foot, 18 gauge, and preferably rubber, like that used for surgical procedures. If you're a little unsure about tube feeding a lamb, don't hesitate to contact an experienced shepherd or veterinarian for assistance. The lamb should show no signs of discomfort as the tube slips down the esophagus and reaches its stomach. It will chew on the tube, but should lie quiet when the tube is in place. If the lamb coughs, rolls its eyes, struggles and calls out as you are inserting the tube, then withdraw it immediately; you've probably put it down the windpipe by mistake. The length of the tube should indicate whether or not the stomach has been reached. Most tubes are of the length such that there will be 2 to 3 inches sticking out of the lamb's mouth once the tube is fully inserted.

The importance of colostrum for newborn lambs cannot be overstated. Lambs raised on the ewe or raised artificially must have colostrum as a critical ingredient for survival. Colostrum is the first milk produced by the ewe. Not only is it high in energy and protein, but most importantly, it is rich in antibodies and globulins, which are critical for protection of newborn lambs from infectious disease. Lambs must receive colostrum within the first 18 to 24 hours of life. After 24 to 36 hours, the antibodies can no longer be absorbed across the wall of the small intestines. Lambs destined to be reared artificially should be allowed to nurse their mother for up to six hours or be supplemented with colostrum from a bottle or stomach tube. If the ewe has perished and in the event you do not have any frozen colostrum from your flock use an artificial colostrum designed for sheep. Obviously this should be ordered ahead of time but you can store it in the freezer.

This can be handy if you live in a northern climate to speed the drying of a chilled lamb. Take care that you do not burn the lamb. Dry with clean towels before using the hair dryer. Allow the ewe to clean off her lamb if possible as she will be bonding to her offspring at this time but take care to monitor the situation in bitter weather. You may need to help her if it is very cold and the lamb is in danger of being chilled. Keep clean terry cloth towels in your lambing kit as well.

Use with care in the event you may have to pull a lamb

Good Luck with your Lambing!

Never substitute advice from a website for proper council from a certified vet.

|

Shepherds Crooks USA

Please Read

This page is only a guide and a starting point. There are hundreds of sites on Line with more in depth information but remember nothing is a substitute for the advice of an experienced veterinarian. Always contact your vet for advice on ovine health issues great and small. We have here only a few ideas to help you understand issues of health concerning domestic sheep. We are not trained vets and we do not hold degrees in science. Medications vary from country to country as do laws governing disease and pharmaceuticals. Always research what is legal and common practice in your region.

copyright 2002 , Jim & Beth Boyle, All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn