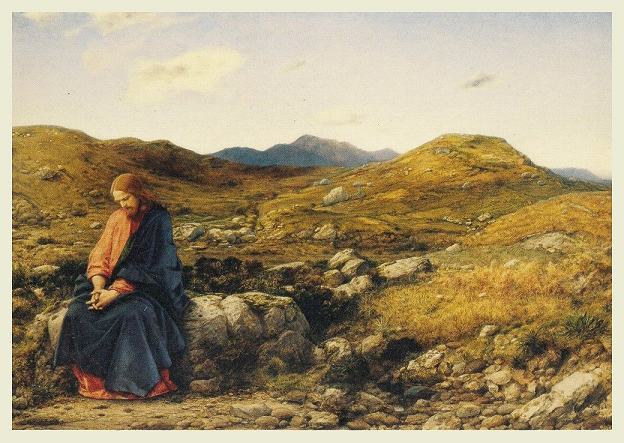

Christ by William Dyce

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland 2004

Christ as the Man of Sorrows

c 1860

Materials: Oil on millboard

by William Dyce

In 1860, William Dyce exhibited his painting The Man of Sorrows at the Royal Academy. This work depicts Christ during his fast of forty days and forty nights. He sits on a natural stone bench, hands folded gently together, head bowed, and facing the lower left-hand corner of the painting as rocky wild grass-covered hills lay still behind him. He sits in meditation.

In the catalogue and on its frame, Dyce quoted part of a poem written by his friend and fellow Anglican High Churchman John Keble, entitled "Ash Wednesday." Keble's poem begins by sermonizing Christ's fast of forty days and forty nights. He speaks directly to members and followers of the Church, questioning how people deal with temptation.

Thus oft the mourner's wayward heart

Tempts him to hide his grief and die

Too feeble for Confessions's smart,

Too proud to bear a pitying eye.

Keble then proceeds to invoke images of the holy: glimmering stars from the eternal house above, Angels looking upon kneeling sinners, and on to He who in secret sees; it is at this point that Dyce quotes.

As, when upon His drooping head

His Father's light was pour'd from heaven,

What time, unsheltered and unfed,

Far in the wild His steps were driven.

High thoughts were with Him in that hour,

Untold, unspeakable on earth.

Dyce captures these lines in a notable way, combining his High Church influences with Pre-Raphaelitism. He meticulously records the granite rocks and wild grass of the barren hills. With his placement of Christ he gives faculty for the viewer to connect with Christ's suffering in this natural setting.

Questions

1. Dyce tells a narrative through a landscape and a conventional Christ. In Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents and Hunt's The Shadow of Death, the narrative is told by the carefully crafted setting of types and an unconventional Christ. We've discussed typological power. How does Dyce's narrative compare with those told through typology?

2. Like PRB painters who drew inspiration from poetry, Dyce chooses to paint the moment of a specific few lines. However, he hardly exaggerates. Though his subject his heavy, he uses soft light and soft colors. What is going on here?

3. The advance of geology was one of the many shocks to the Bible during the Victorian Era. How do we read this High Churchman's use of realism?

4. Aside from the beauty of nature, there is no allusion to the Holy Spirit or other religious types. How does this dictate the message of the painting?

References

Barringer, Tim. RReading the Pre-Raphaelites. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999.

Keble's poem is drawn from Matthew's words: "And when the tempter approached him, he said, "If indeed you are the Son of God, then command that these stones be made bread. But he (Jesus) answered and said, "It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by the very words that proceed from the mouth of God." Matthew's Gospel (4:3-4)

The Artist, William Dyce

(September 19, 1806, Aberdeen, Scotland – February 14, 1864, London)

Scottish painter and decorator. Son of an Aberdeen doctor, he studied art against his father's will. Sir Thomas Lawrence was so impressed with his talent that he persuaded Dyce to take up painting professionally. He made several trips to Rome, where he was deeply impressed with the aims and ideals of the Nazarenes Overbeck and Cornelius, and also by Italian Renaissance painting. These influences persisted throughout his career. He painted portraits and religious subjects, and several fresco cycles in the House of Lords, Lambeth Palace, Buckingham Palace, Osborne House, and several churches. He was one of the few artists to sympathise with the Pre-Raphaelites. His own works, such as 'Pegwell Bay', and 'Titian's first Essay in Colour' show PRB influences in the realistic detail and bright colours. The latter picture drew praise from Ruskin in 1857 - "Well done, Mr. Dyce! and many times well done!". As he was kept busy by public duties in Government Schools, he did not exhibit a great many pictures. Most were exhibited at the Royal Academy and the Royal Scottish Academy, and some at the British Institution. His style is highly individual, a blend of Nazarene and Pre-Raphaelite ideals, and is always characterised by an innate religious feeling. His studio sale was held at Christie's on May 5, 1865.

Biographical source: 'The Dictionary of Victorian Painters', Christopher Wood, Antique Collectors' Club, 1971.

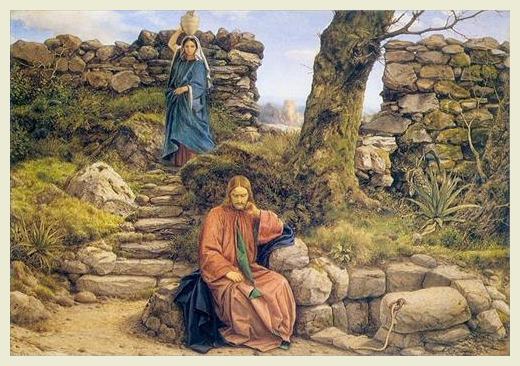

Jesus said to her, “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty. The water that I will give will become in them a spring of water gushing up to eternal life.”

- John 4:13-14

© Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

The Woman of Samaria

C 1860

by William Dyce

Materials: Oil on millboard

Although William Dyce had little direct contact with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he was sympathetic to its aims and practice, and brought the young artists' work to the attention of John Ruskin. Dyce's own work became heavily influenced by Pre-Raphaelite ideas.

'Christ and the Woman of Samaria' depicts The New Testament story in John 4. Seated by a well in Samaria, Jesus converses with a local woman, in itself a gesture of reconciliation between the Jews and Samaritans, who were long-term enemies. While the woman seeks water as a simple necessity of life, Jesus speaks of the living (flowing) water as a sign of eternal life, emanating from God.

Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, Rejoice. Let your gentleness be known to everyone. The Lord is near. Do not worry about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.

- Philippians 4:4-7

Next page

'Feuch air fear coimhead Israil

Cadal chan aom no suain.'

(The Shepherd that keeps Israel, He slumbers not nor sleeps.)