HOME | home

Scottish Blackface | Scottish Blackface II | Scottish Blackface III | Scottish Blackface IV | Scottish Blackface VI | Scottish Blackface VII | Scottish Blackface V | Scottish Blackface VIII | Blackface IX | Blackface X | Scottish Blackface Breeders Guild | Blackface Guild 2 | Sheep Shearing | Photo Essay of Blackface | Piebald or Jacob Sheep | Soay Sheep | The Shepherds Bothy

Blackface X

Old Traditions

By James Zoebel

The Milking Of Ewes And Goats

From

Scottish Country Life

Alexander Fenton

Skene of Hallyard's Manuscript of Husbandrie shows that cheese was commonly made of ewes' milk in his time, and seems to have been preferred to cows' milk cheese, though plenty of that was also made, especially in Gunningham. The difference in quality is reflected by a difference in price. When cows' milk cheese cost \f- a stone in Tweeddale in 1794, ewes' milk cheese cost 7/-.9 With butter, the positions were reversed, and ewes' milk butter was generally used with tar for smearing sheep, like the second-rate cows' milk butter that was paid for rent.

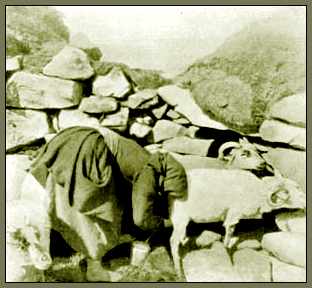

By the end of the eighteenth century, the milking of ewes had virtually come to an end, surviving longest in eastern Scotland in areas like the Lam-mermuirs where farmers still milked ewes in 1794 to get butter for sheep-salve,and cheese for retail to the shops. In the Highlands, Samuel Johnson saw both goats and sheep being milked in Skye in 1775. A meal or single milking of goats' milk amounted to a quart, and was thinner than cows' milk; that of a ewe amounted to a pint, was thicker, and was not consumed unless boiled. All the goats' milk, if not used in liquid form, was made into cheese, either by itself, or mixed with ewes' milk and sometimes warm cows' milk. A nineteenth-century description of the Glenlyon shielings in Perthshire speaks of four kinds of cheese - of cow, sheep or goat milk alone, or of all three combined.

In the Lowland areas the folding and milking of ewes for cheese-making came to an end by about 1800, the custom surviving longest in higher parts like the Lammermuirs and the head o fAnnandale. In the Highlands there was a fifty year time lag, and though the introduction of the Border sheep breeds effectively ended the old custom, nevertheless in Rannoch and the Braes of Lochaber goats continued to be kept for milk and cheese. Even with the Blackface, the old tradition died hard, for it was common to gather the ewes into tanks once or twice after weaning to milk them, to keep the household supplied with cheese.

Though the salted butter supplied by Renfrewshire farmers to Glasgow was said to keep fresh for a year, butter is nevertheless a perishable commodity, easily affected by heat. Women taking fresh butter to market would wrap it in a rhubarb leaf to keep it cool, or immerse it in a well, perhaps leaving the name 'Butter Wallie' behind as a souvenir. The same need for coolness and for longer-term preservation must explain the numerous finds of 'bog-butter' that have turned up in various parts of Scotland, often wrapped in a cloth and put in a wooden container. A sample from Poolewe was wrapped in the outer bark of a tree." Bog-butter appears to have been unsalted, hence the need to immerse it in a boggy pool, where the owner lost it and where peat solidified over it in the course of time. Some of it contains many cow hairs, like butter seen on a croft in a northern island in the IQ50S, when a knife blade had to be taken through it several times to clear it. This process had a name - to hair the butter - which goes back at least to 1700 and was known from Peebles to the Northern Isles.

The old way of churning butter in the shielings and in the houses of the wintertowns was to put the milk in a small wooden tub or earlier an earthenware craggan covered with a tightly tied sheep- or goat's skin. Then, according to a manuscript account of 1768 relating to Skye, two women seated opposite each other tipped it alternately half up and then dashed it back down, till the milk broke into butter against the sides. It could take nine or ten hours. Straw was used to cushion the shock or, in the shielings, the work was done on the bed. According to a report from Loch Ailort, butter was sometimes made by shaking in a leather bag. A Moray method, said to have lasted till about 1770, was simply to whisk the milk with the bare arm in an iron pot. Such methods remained long where much of the community work depended on women, and upright wooden plunge-chums were still innovations in the islands quite late in the nineteenth century.

|

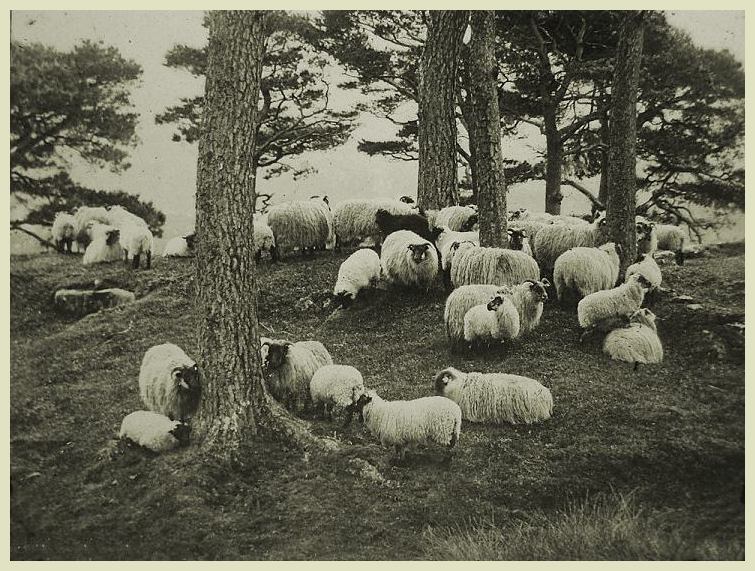

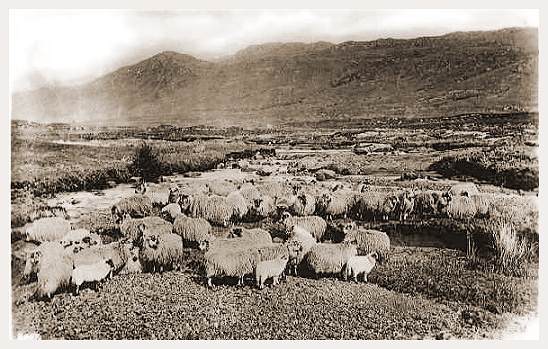

After the shearing, Auchallater Farm

Hill Shepherd's Reference Books

A Shepherd Remembers,Reminiscences Of A Border Shepherd, by Andrew Purves

A Stick, Hill Boots And A Good Collie Dog, A Shepherd's Life Fifty Years Ago, by Ben Coutts

Isolation Shepherd by Iain R. Thomson

Shepherd's Delight, The Best Of Tom Duncan by Tom Duncan

Scottish Country Life by Alexander Fenton

At Home In The Hills, Sense Of Place In The Scottish Borders by John N. Gray

Glencoe And Beyond, The Sheep-Farming Years, 1780-1830 by I. S. MacDonald

Herds And Hinds, Farm Labour In Lowland Scotland, 1900-1939, by Richard Anthony

|

copyright 2002 , Jim & Beth Boyle, All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn