HOME | home

Scottish Blackface | Scottish Blackface II | Scottish Blackface III | Scottish Blackface IV | Scottish Blackface VI | Scottish Blackface VII | Scottish Blackface V | Scottish Blackface VIII | Blackface IX | Blackface X | Scottish Blackface Breeders Guild | Blackface Guild 2 | Sheep Shearing | Photo Essay of Blackface | Piebald or Jacob Sheep | Soay Sheep | The Shepherds Bothy

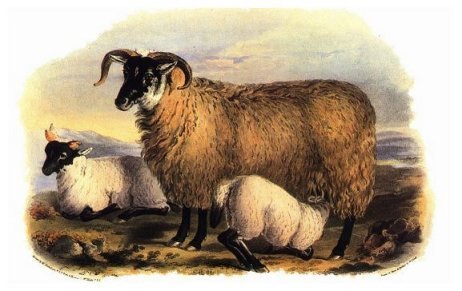

Scottish Blackface VII

I highly Recommend this book!

200 YEARS OF BRITISH FARM LIVESTOCK

Stephen J.G. Hall & Juliet Clutton-Brock

The Natural History Museum,

London, 1989

SHEEP OF HILL AND MOUNTAIN

Scottish Blackface

It is impossible to trace their origin, there being no tradition of the sheep here being ever of a different kind. Thus wrote James Naismyth, in 1795, of the black-faced horned moorland sheep of the uplands of Strathclyde. These sheep were also known as Lintons, after the market at West Linton where they were sold.

Even in Naismyth's day different kinds of black-faced moorland sheep were known, among them the Galloway sheep with a shorter but finer fleece and more white on the face. Today several races are recognized; the Lanark, Newton Stewart, Perth, and Lewis, all differing particularly in fleece characteristics but also in meat conformation. The Lewis is small and lean, while the Lanark is the largest. The Perth and the Lanark have the heaviest fleeces. The Newton Stewart is thought to have been the most improved, but it is no less hardy than the others. Within the breed there are three types of wool; Mattress, staple length 8 inches (20cm). Medium, 6 inches (15 cm), and Short Fine, 3 to, 5 inches (8 to 13 cm), with differences in the thickness and softness of the wool. Today the Blackface produces nearly half of Scotland's wool, for uses ranging from carpet manufacture to the weaving of Harris tweed.The Blackface definitely came from south of the Border but details of its progress north are unknown, and the sheep which it superseded, called the Dunface or the Old Scottish Short-wool, is also something of a mystery. Relics of this race presumably endowed the Newton Stewart and the Lewis Blackfaces with the relatively fine fleeces they possess today.

The husbandry system of the south-west, based on the Old Scottish Short-wool, was completely swept away when the Blackface took over. The process was repeated, starting around 1752, when the new sheep invaded the Scottish Highlands. In that year John Campbell took Blackface sheep from Ayrshire to Dunbartonshire. The Blackface was very rapidly established on the central and west Highlands because previously the emphasis had been on cattle and

the hills were only pastured in summer. It took longer for the eastern Grampians and north-east uplands to be taken over as there were large numbers of native sheep to be replaced but by 1840 the native breeds and their husbandry were only to be found in Orkney, Shetland,and some of the Outer Hebrides.

At the same time, rivalry between the Cheviot and the Blackface was intense. Initially the Cheviot gained ground as its better wool found a ready market when the Napoleonic Wars cut off the supply of fine Spanish wool. By 1860 Cheviots made up nearly half of the hill sheep of Scotland, with the Blackface strong on the higher and harsher hills. The severe winter earlythat year did far greater damage to Cheviot flocks than to the Blackfaces, especially in the southern uplands, and the Blackface staged a resurgence there. Cheviots retained their hold on the country north of Inverness and were at their most widespread in 1870. However, after this high point Cheviots declined as cheap fine wool was imported and severe winters in the1870s accelerated the process. The meat market also favoured the Blackface; lambs of this breed were more easily finished for the growing demand for high quality lamb. Throughout its history, the Blackface has kept its reputation as one of the hardiest Britishbreeds and it was in furtherance of this attribute that its promoters refused to have anything to do with pedigree breeding, flock books or a breed society until 1901. They felt that fashion points could easily become paramount, to the detriment of the breed. Even so, on many occasions particular rams or flocks have commanded enormous prices. Whether this has been the result of fashion or of

a genuine commercial requirement is debatable.

There are very many factors to be borne in mind when selecting a hill ram. He must be able to pass on good characteristics of feet and teeth, fleece and meat conformation. Unlike the Cheviot, the Blackface is expected to cope with a tough diet including heather, and to obtain enough food long distances must be covered, usually over difficult country. With between five and ten per cent of the income of the typical hill farmer coming from wool, the most remuner-

ative fleece must be bred for, that will protect the sheep against the weather. Since half of his lambs will be male, to be castrated and sold for meat, the ram must also be able to endow them with good fleshing characteristics. Perhaps therefore it is not surprising that the right Blackface ram can be worth over 40 000 guineas to his purchaser. Such prices are paid for rams that are going to be used in elite flocks which themselves supply rams to the commercial

hill farms.

The husbandry system of Blackface flocks shows very many local variations, developed over decades in response to local conditions. The general pattern, however, is for old ewes to be sold (drafted) from the hill farms with their tough herbage to lush grassland often very far from their native hills. This is a valuable trade for the hill farmer. These drafted sheep are the main source of the cross-bred ewes which are currently the most widespread lowland sheep.

|

Two Hundred Years of British Farm Livestock (Paperback)

Stephen J.G. Hall and Juliet Clutton-Brock

A description of the development of British breeds over the last two hundred years, recording what is known of their history. The text is accompanied by many fascinating pictures, many in colour, making the book a delight. If you are looking for a presentation volume this is it!

British Museum (Natural History)

Cromwell Rd, London SW7 5BD

`

copyright 2002 , Jim & Beth Boyle, All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn