HOME | home

Iron on the Hearth | Iron, Cast and Forged | Cast Iron Cooking 4 | Copperware | Copper and Brassware 2 | Brass Alcohol Stove | Pipe Smoking | Tobacco the Indian Weed | Women's Pipes | Clay Pipe Collection | Pipes2 | pipes3 | Pipes4 | Pipe Tampers | Early Lighting 1 | Early Lighting 2 | Early Lighting 3 | Early Lighting 4 | Early Lighting 5 | Early Lighting 6 | My Lamps | Center Draft Lamps | Center Draft Lamps II | Center Drafts III | Miners lamps | Matches and Match Safes

Copperware

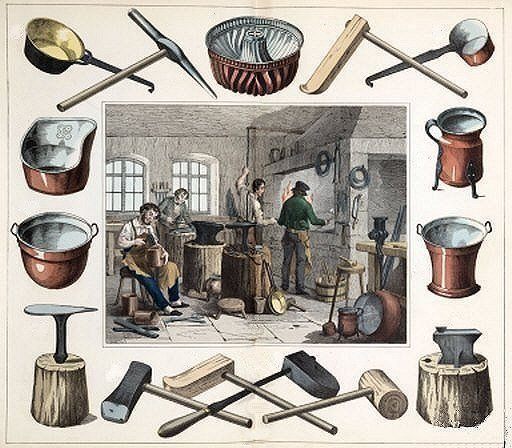

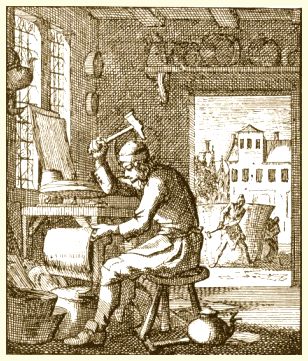

Coppersmiths 1840

Copper and Brass Cookware

Copper is the best practical conductor of heat for cooking. Professionals love it because of its quick reaction time. It cooks faster, and it also cooks better because of its uniform conductivity, as it surrounds your food with heat. The primary advantage of copper is that it requires only low to moderate heat to obtain the best results. And its conductivity makes it especially responsive to almost every cooking need. Copper has about ten times the heat conductivity of stainless and glass, and twice that of aluminum. So watch the amount of heat you give it. Let me repeat that: watch the amount of heat you give it, at least until you become accustomed to its even, fast acting conductivity. Stainless and nickel linings in French copper are very durable, by comparison to tin linings, and also very expensive. In general, we recommend tin for all copper pans. However, because tin melts at about 450°F we often recommend stainless for frying (and maybe sauté) pans, which receive more direct heat that is not dispersed by liquids (unlike sauce pans, stock pots, etc.), thus preventing the damage that accidental overheating might cause. Even today the best copper/ tin lined pans are lined by hand, and will display some brush strokes as a result. Lining by hand insures thicker coats of tin, that will last much, much, much longer than pans that are electroplated. Unlined copper works best for egg whites, which it helps to make thicker and peak longer. Zabaglione is one of the recipes most commonly made in an unlined copper pan. Unlined copper is also widely used in the candy industry. Confectionery prepared in unlined copper doesn't react with copper, and takes advantage of the quick, high heat that the confectioner needs.

Early Man's work with Copper, Brass, & Bronze

While copper ores in small amounts are common worldwide, there are a few places where good copper ore in easily smelted form is abundant. For the ancient world, the island of Cyprus was the main supplier of copper -- indeed our word copper derives from the name Cyprus. Cyprus not only had the ores, but as an island in the eastern Mediterranean, it was easily reached by ships from Egypt, Greece, and somewhat more distant Rome.

Tin was more of a problem. The only known large deposits of tin in the ancient world were in western Great Britain, an island like Cyprus, but in the Atlantic instead of the Mediterranean and far to the west of Egypt and Greece. Long trade routes for tin began by crossing the English Channel to Gaul (France) and continuing overland to Mediterranean ports such as Massalia (Marseilles) before loading goods onto sailing freighters. Such travel contributed to the high cost of tin, and therefore of bronze. When the Romans near the end of the republic occupied Britain, an occupation that lasted for about 400 years, their main goal was probably control of the tin trade.

Bronze is a relatively strong and corrosion-resistant metal, but people in Antiquity also used the other main alloy of copper, brass. Today brass is known to be made from copper and zinc, but zinc was not discovered until the 13th century in India and not produced in the West until its rediscovery in 1746. However, as early as the 16th century some alchemists were aware that there was a metal at the heart of the mineral known by the ancients as calamine -- recognized today as two different zinc-based compounds, zinc carbonate and zinc sulfate. The earliest brass was made by smelting copper ores or copper with calamine; according to one early source, brass smelting was first accomplished in Anatolia (Turkey) by a people called the Mossynoikoi. The earliest brass item known today dates from 20 c

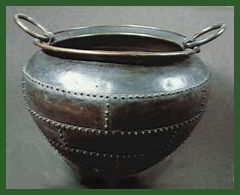

Bronze Age Caldron made of sheets of Bronze from Ireland

Brass is as useful as bronze and more attractive; its golden shininess caused the ancients to consider it a form of precious metal. However, all the "brazen" items mentioned in the Bible were probably made from bronze, not brass. The words bronze and brass were used indiscriminately until recent times, and even today certain alloys of copper and zinc that should be called brasses are known as bronzes. Although zinc is more common than tin, lack of clear recognition of zinc may have contributed to its late arrival and rarity in early times. Today brass is more commonly used than bronze.

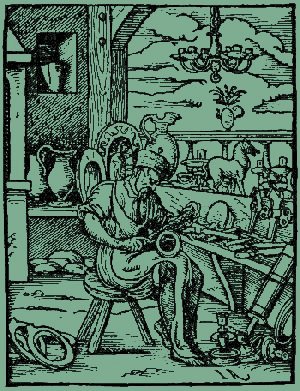

15th Century Coppersmith

|

Care of Tin-Coated Copper and Brass Cookware

Most Copper and Brass Cookware is lined with Tin. Stainless and nickel linings in French copper are very durable, by comparison to tin linings, and also very expensive. Few people can purchase this copperware to use in their daily lives due to cost. Pans, Pots, mugs and drinking vessels are all commonly lined with tin. Tin is not reactive to acidic foods, and can be easily refurbished. Tin (Sn) is a relatively soft and ductile metal with a silvery white color. It has a density of 7.29 grams per cubic centimeter, a low melting point of 231.88° C (449.38° F), and a high boiling point of 2,625° C (4,757° F). Tin cans are in fact made from iron that is dipped in tin to prevent rusting. Tin is still the preferred choice of lining in sauce pans and stock pots made of copper and steel, and in steel baking molds. Tinned Steel is steel covered with a thin layer of tin. The tin protects the steel against rust, and it prevents acidic foods from reacting with the steel. Even though tin melts at about 450°F (c. 230°C), an oven can be set to higher temperatures or burners at higher heat for short periods of time without problems, as long as there is food and liquid in the pan. The food and liquid absorb heat and keep the tin from melting. The majority of recipes call for temperatures that will not harm a tin lined utensil that is properly used. Whether on the stovetop or in the oven, the principle is the same: prolonged (and unnecessary) high heat will damage the lining any quality cooking utensil, high heat is rarely necessary, and the best results come from moderate heat.

Early Dutch Engraving of a Coppersmith or Koperslager

Caring for tin-lined cookware. Some simple routines in use and care will ensure the longevity of the lining.

Use only wood, nylon, silicone or other non-metallic utensils to stir and scrape. The melting point of tin is approximately 450°F. Do not leave a pan over heat without moist food or some liquid inside. Tin is a soft metal and should be cleaned with a dishcloth or sponge. Never use abrasive cleaning materials, such as metal scouring pads or metal scrapers. As with all metal utensils, avoid using cleansers and detergents that contain high percentages of free alkali or acid. Tin is reactive to tri-sodium phosphate, meta-silicate and chlorine. Avoid using detergents or cleansers containing high quantities of these materials. Rinse thoroughly after washing and dry to avoid spotting. Tinned steel should be dried thoroughly immediately after washing to prevent rust from forming on spots where the tin might have worn off the steel, and around edges where turned, soldered or welded. Store tinned items in a dry location.

More info...

As tinned utensils get older, they become darker in color. This is normal and in no way interferes with the properties of the metal. Often, the darkness caused by dried, stuck-on food is mistaken for the bare copper or steel. To test this, wet a paper towel and gently rub a small spot with a little cleanser. If it becomes silver in color, the color is dried foodstuffs; otherwise you will clearly see the copper or steel.

Retinning is not absolutely necessary in all cases. In the case of copper, the tin prevents reaction with acidic foods. If you're not cooking acidic foods, then it's not necessary to have the tin lining. Also, if the copper pot is going to be subjected to very high temperatures, such as for making hard candy, the copper needs to be bare in order to support the high temperatures. And bare copper is desirable in making meringues, because of its reaction to egg whites, which makes them peak faster and longer. In the case of steel, the tin coating basically prevents rusting and reaction with acidic foods. If you are using the pan for baking and you keep it dry and well oiled when in storage, retinning, though desirable, is not necessary.

For retinning services in the USA

Two unlined vessels, a copper bowl for beating eggs and a preserving kettle of brass for making jelly etc.

Method for Determining if Your Copper Pan has Lost its Lining

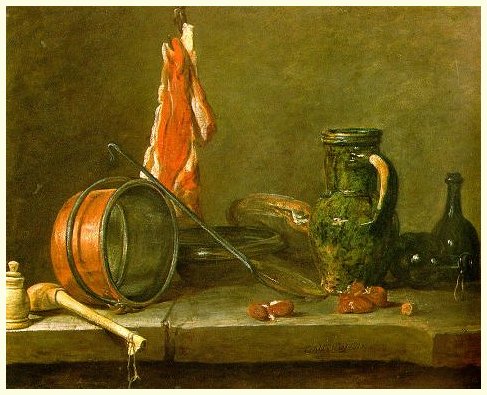

*Chardin

Here's a simple method for determining if your copper pan has lost its lining. Lightly rub a bit of cleanser on a spot in the lining with a wet paper or cloth towel. If you see silver, your pan is ok. If you see copper showing through, then you might want to consider retinning.

How much shows through can help you determine whether or not to pursue retinning. If it's just scratches, and you generally don't use the pan filled with highly acidic foods, then you can wait. If you do cook highly acidic foods regularly (like making sauce with plum tomatoes) and more copper than just scratches is obvious, we recommend retinning. If you notice discoloration of food as you cook, then we also recommend retinning.

Lining on lids generally doesn't do much, as the lid doesn't come in contact with food. Still, if a lot of copper is showing, we recommend retinning.

*Lean Diet, Chardin 1731

copper poisoning

Acute copper poisoning is a rare event !

"Acute copper poisoning is a rare event, largely restricted to the accidental drinking of solutions of copper nitrate or copper sulphate which should be kept out of easy access in the home. These and organic copper salts are powerful emetics and in advertent large doses are normally rejected by vomiting. Chronic copper poisoning is also very rare and the few reports refer to patients with liver disease. The capacity for healthy human livers to excrete copper is considerable and it is primarily for this reason that no cases of chronic copper poisoning have been reported. Acute copper poisoning occurs in man when at least several grams of copper sulfate are ingested or when acidic food or drink –vinegar, carbonated beverages, or citrus juices – have had prolonged contact with the metal . . . Eight children and one of two adults who drank orange flavored beverage refrigerated overnight in a brass pot became nauseated, and several of the children vomited."

Beware of children or animals ingesting:

*Pool and hot tub treatment Chemicals

*Aquarium treatments

*Products to treat foot rot in Sheep and Cattle

*Algaecides

*Copper Naphthenate

|

LINKS

For detailed info on copper and brass:

Great Italian Copper Piece, probably designed for olive oil

The 2 paintings above on this page are by Chardin, Jean-Baptiste-Siméon (1699-1779):

*The Copper Drinking Fountain c. 1734

*A "Lean Diet" with Cooking Utensils c.17.31

copyright 2002 , Jim & Beth Boyle, All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn