HOME | home

Iron on the Hearth | Iron, Cast and Forged | Cast Iron Cooking 4 | Copperware | Copper and Brassware 2 | Brass Alcohol Stove | Pipe Smoking | Tobacco the Indian Weed | Women's Pipes | Clay Pipe Collection | Pipes2 | pipes3 | Pipes4 | Pipe Tampers | Early Lighting 1 | Early Lighting 2 | Early Lighting 3 | Early Lighting 4 | Early Lighting 5 | Early Lighting 6 | My Lamps | Center Draft Lamps | Center Draft Lamps II | Center Drafts III | Miners lamps | Matches and Match Safes

Early Lighting 1

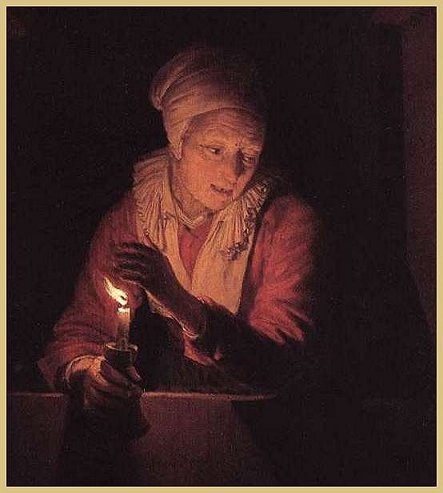

DOU, Gerrit

Old Woman with a Candle

1661

From about the sixteenth century onwards, living standards improved

greatly as evidenced by the increasing availability of candlesticks

and candleholders and their appearance in middle class households. At

that time, candles were usually sold by the pound in bundles of eight,

ten, or twelve.

To Drive Away The Darkness

By Beth Maxwell Boyle

The word "candle" comes down to us from the Latin candere, meaning "to shine." The first reliable mention of a candle was made in the first century A.D. by Pliny the Younger. Candles from the beginning of their existence were either made of tallow or wax. Tallow and beeswax candles were important sources of light for the Romans who introduced the dipped candle, rolled and bleached wax candles, and their style of socket candlesticks to Britain. Before this, rushlights were used to light the British homes and in northern Scotland people used the candle-fir. Candles were either dipped or molded. Beeswax could also be rolled around a wick. In the seventeenth century, colonists in America discovered that a pleasant berry scented wax was produced by boiling the berries of the bayberry tree.

Early bronze or brass candlesticks

Relatively few candles were used in private homes until about the 14th Century, they were, however, an important symbol of the Christian Church. In early America candles were hand made of tallow or animal fat with exception to those made of Bayberry or Beeswax. The latter were very expensive and not used by the average household. Candle making as we know it began in the 13th. Century when traveling chandlers went door to door making dipped tapers from their clients tallow or beeswax (wealthier folk). From about the sixteenth century onwards, living standards improved greatly as evidenced by the increasing availability of candlesticks and candleholders and their appearance in middle class households. At that time, candles were usually sold by the pound in bundles of eight, ten, or twelve.The first use of molds for candle making was in 15th. Century Paris. Tallow candles were made either using the dipping method or using candle molds. Candle molds were most often made of tin but wood copper and other materials were also used. Tallow candles burned with an odor and were usually stored in candle boxes of tin or wood to keep out rodents and other creatures who were eager to consume them.

The tallow of cattle or sheep was used most often to make candles. Pork tallow is too drippy and smelly. Most candles sold today are made of paraffin derived from petroleum. It is easy to forget that the candles of yesteryear were fatty drippy and much more likely to need attending. Fine beeswax candles were the exception but beeswax was a very costly commodity. Even today beeswax candles are much more costly but it cannot be denied they are the finest candles and burn with a truly wonderful smell. Early wicks were strands of peeled Scarpas, a rush-like plant, or two rolled pieces of papyrus soaked with sulphur. Later, in the eighteenth century twisted cotton strands and then plaited cotton wicks were used.

The Frenchman Cambaceres discovered that the plaited wick, as compared to the twisted wick, burned most similarly to the peeled rush wick. When lit, the plaited wick curled over into the outer mantel of the flame where it was consumed, thereby self-trimming itself which caused less smoke. The single plaited wick was the easiest to use for molded candles. Plaited cotton wick could be purchased by the yard by the mid-eighteenth century.

Wellmade reproduction made in India

Here we are burning a splint of candlewood or fatwood as it is sometimes called. These also cold hold rushlights that were made from the soft rush and common rush plants. The stalks or stems were gathered, soaked, and then the outside “skin” peeled away revealing the inner rib. After drying the pith, it was then soaked in melted animal fat or fish oil in preparation for burning.

Fat lamps were used extensively as well, in most households, as they were the cheapest way of lighting the home. Fish oil and animal fat were commonly used. Brass, wood, pewter, clay, and iron were all very common materials for candlesticks. Wealthy households might have silver and brass candlesticks while the common folk would have wooden, iron, pottery or pewter candlesticks and holders. Many candle holders were designed to hold both rushes or wood splints as well as candles giving the owner a choice of lighting materials. Fat wood, candlewood, or sappy pine splints were held fast in these devices and used as a cheap way of lighting the home and stable. Specially pealed and prepared rushes were also used to burn in such iron holders to give light. Candlesticks could be placed on a table or stand but many tall types were made that stood on the floor. Often these were adjustable so the user could illuminate their work or what they were reading.

Reproduction tin lantern and courting candle

Candle lanterns allowed light to be portable and many styles were made both in Europe and America of tin, iron, wood, glass and horn. One could venture out to the stable or the woodpile without loosing ones flame with the protection of a lantern. Punched tin lanterns were very common and a fairly cheap lantern type. These gave off a faint light but if kicked over in the cowshed or hay mow they would not start a fire. Panels of glass were sometimes used in tin and wood lanterns to allow for better illumination but more often thin translucent sheets of flattened ,cattle horn were used. These too were less breakable and also more available to the craftsman in the out lying areas and smaller villages. The name lantern actually comes from the name "Lanthorn" because of the use of cowhorn that light could pass through.

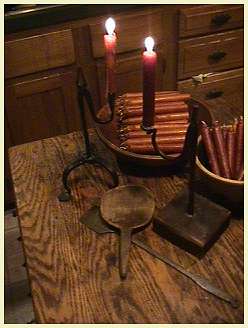

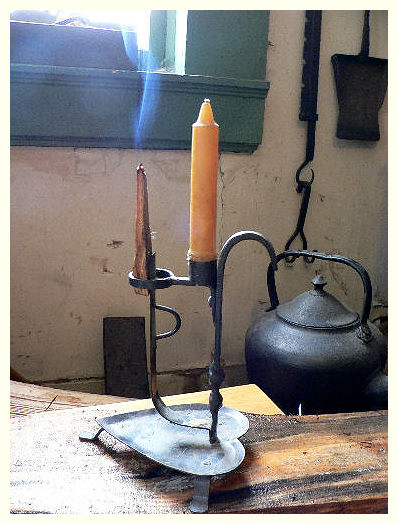

Two reproduction rushlights with candle sockets

Peermen and Rushlights belong to the same family. Both are of very ancient design and serve about the same purpose but work in slightly different ways. The essential difference between them being the purpose of the peerman is to burn candle fir or fatwood as it was often was called in early America while the rushlight burns prepared rushes collected in the countryside. Fir candles are long splints of wood stripped along the grain of fallen fir trees. These were once commonplace in the pine forested countries of Northern Europe. In the U.K. they only existed in Scotland and to a lesser extent in Northern Ireland. Unlike the meadow rushes used for illumination, fir candles require no preparation and due to their high natural oil content burn quicker. They are therefore burned in the vertical position. Nearly all peermen incorporate a spring but very few rushlights do because pressure can crush the rush. Despite the fact that the candle tax was abolished in 1831 in the UK, rushlights continued to be produced well into the Victorian era. Almost all of the later ones incorporate a candle socket so that more than one type of light could be used. Some early ones also incorporated this feature as well. Peerman likewise sometimes have a socket for a tallow candle. Once these devices progressed from the 18th Century into the machine age they became more refined and are very difficult to date. No one has established when they became obsolete for certain. They may well have carried on for al lot longer than historians once commonly thought. After all, when common folk had a source of good bright light which was completely free, why would they want to change and start buying expensive tallow candles? Scotland consisted largely of rural communities often very isolated from one another. It is quite possible that the nearest chandler 's shop was a days walk away. New England was very much the same. Many fine examples of early lighting devices have been discovered in Maine. It is still one of the best places to find early iron work in the USA.

A Peerman, this is an artful reproduction made in India

The betty Lamp evolved from simple clay lamps that were used as long ago as 6,000 B.C. Latter these simple spout lamps were made of iron, copper and bronze. They burned fish oil or fat trimmings and had wicks of twisted cloth. These lamps were smoky, smelly, and the wicks often drew up oil quicker than it burned, allowing the surplus to spill over the sides of the lamp onto anything that rested beneath them. Some iron lamps were fitted with two pans so that the second pan could catch the drippings and keep them from over flowing but they required constant attention. A common name for these was crusie lamp. The wicks were free floating in a spout but still often fell below the surface of the fat and had to be picked back out with a pickwick.

The Rushlight or Rush Candle of Old England

From The Rushlight, Vol. 1. No. 4; Feb. 1935

Readers of Shakespeare and Milton, of Scott and Dickens, of Charlotte Bronte and other writers, are probably familiar with the rushlight of English literature, but few of them perhaps have any distinct mental picture of it and how it was made. Figures given here are from the years between 1750 and 1800.

The common Soft or Candle Rush of Europe is identical with the common Bog, Soft or Water Rush (Juncus effusus L.) of our own Worcester County, where it grows freely in wet meadows, and along brooks and the borders of ponds. The Candle Rush has a round, green, erect stem up to four feet tall, filled with a soft, white pith. There are no leaves, but several inches below the pointed tip of the plant is a many-branched cluster of small inconspicuous flowers.

The best time to collect the rushes for candle-making was in the summer or early fall. As soon as the rushes were cut, they were put to soak, so that the peel or outer skin would strip easily. Small children, old people, and even the blind became very proficient in removing this skin, always leaving narrow strip to hold the pith together. When this was done, the rushes were left out on the grass to bleach and to collect dew for several nights; they were then dried in the sun. All the fats and grease of the household were saved, and if a little beeswax or mutton suet could be added to the mixture, it gave a clearer light and burned longer. The rushes were dipped in this boiling mixture, and when carefully done gave a good clear light.

A rush two and a half feet long would burn about an hour and larger ones up to an hour and a quarter. A pound of rushes, weighed and dipped, would contain over 1600 individuals and would cost about three shillings or 1-11 of a farthing apiece. Allowing an average of only half an hour for each rush, large and small, to burn, this would give over 800 hours of light, or 33 entire days. A thrifty housewife could get 5 1/2 hours of rushlight for a single farthing, and a pound and a half of rushlights would last a frugal family an entire year; for the working people went to bed and arose by daylight.

Taken from Worcester Magazine. Its author was Norman P. Woodward, Botanist, and it was sent to THE RUSHLIGHT by Mrs. Frank H. Dillaby.

Pictured here, Antique Crusie on left, Antique Betty lamp on right

The betty evolved from the simple crusie lamp. A wick-holder in the base was added to the design which channeled the drippings from the wick back into the bowl of the lamp where it could eventually be consumed. A cover was added to confine heat, decrease smoke, and make the oil burn efficiently. These changes also reduced the chance of dangerous house fires. Unlike the crusie, a second pan was not needed on a betty lamp. A handle attached to the opposite end from the flame that curved up to a short chain was attached to most betty lamps as well. The chains were fitted with a hook on one end for hanging the lamp and a pick for adjusting the wick. This better lamp design, named the betty, from the German word, "besser" or "bete," meaning "to make better," produced good light for its time. The betty lamp was used widely by the American colonists and by Europeans. Sometimes the betty lamp was hung from a lamp stand that was on a table or a tall iron or wooden stand that rested on the floor. Another form of elevating the betty lamp was a turned wood or tin pedestal that sat on the table. On that sat the lamp and illuminated the work surface or reading material of the person sitting there.

copyright 2002 , Jim & Beth Boyle, All Rights Reserved

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn

|

International Association of Collectors & Students of Historic Lighting

Please note: We are not able to give appraisals of the antiques you plan to sell on eBay! We will help serious collectors when we can with information. Enquiries are welcome from fellow collectors and historians, but please, we do not have the will or expertise to evaluate antiques for resale.

No part of this website may be used for any purpose ( including using images )

without written consent from The Rams Horn